Discovery of money

How the new culture was making money?

Experts: Yuri Saprykin

How the new culture was making money?

Experts: Yuri Saprykin

How the new culture was making money?

In 1995, a Russian branch of the Open Society Foundations opened. American businessman George Soros’ philantropic organization. Soros’ foundation will then be attacked mercilessly for importing alien values into Russia. Or it will be thanked for helping some non-profits survive after they lost state funding and would have otherwise disappeared.

Either way, it may have been the first example of systematic funding of culture, especially non-profit cultural activities. The state had given up on this, and the private sector still had to figure it out.

In Late Soviet culture, money is a completely new concern. In the Soviet era, people just didn’t have to think about it: money was either a lifelong guarantee, a reward for loyalty, or something earned at a day job while the rest of one’s time went to purely non-commercial art.

Yet already during Perestroika one learns that artworks – even radical, underground ones – are products that sell well in the market. The first sensations, the first shocks in this industry are connected precisely with money from the West.

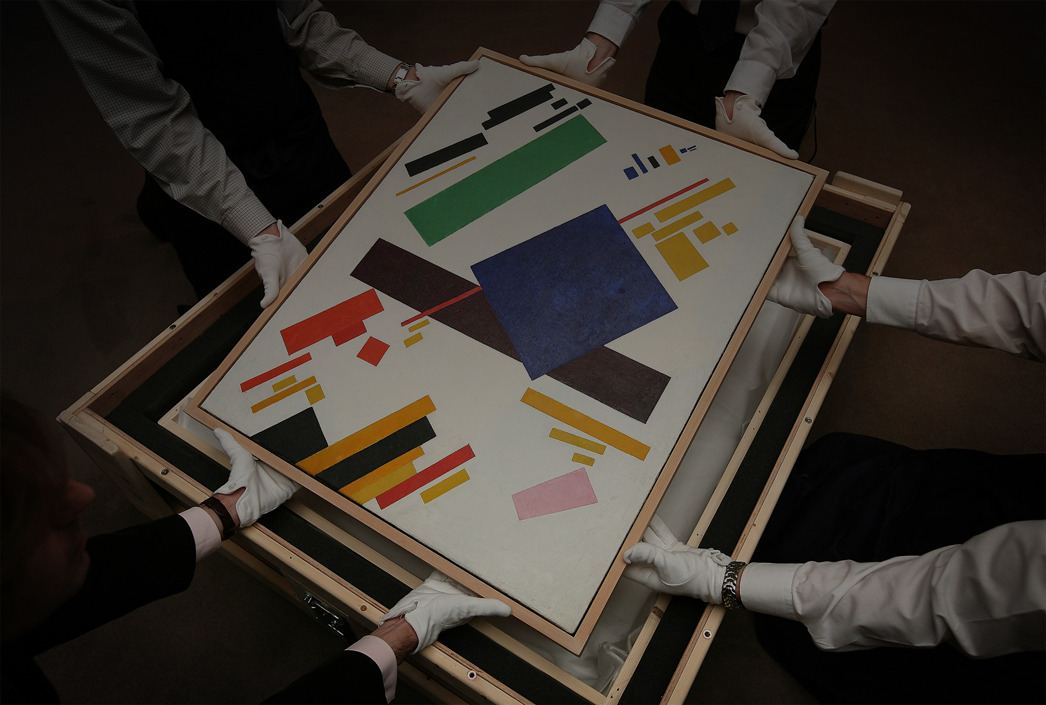

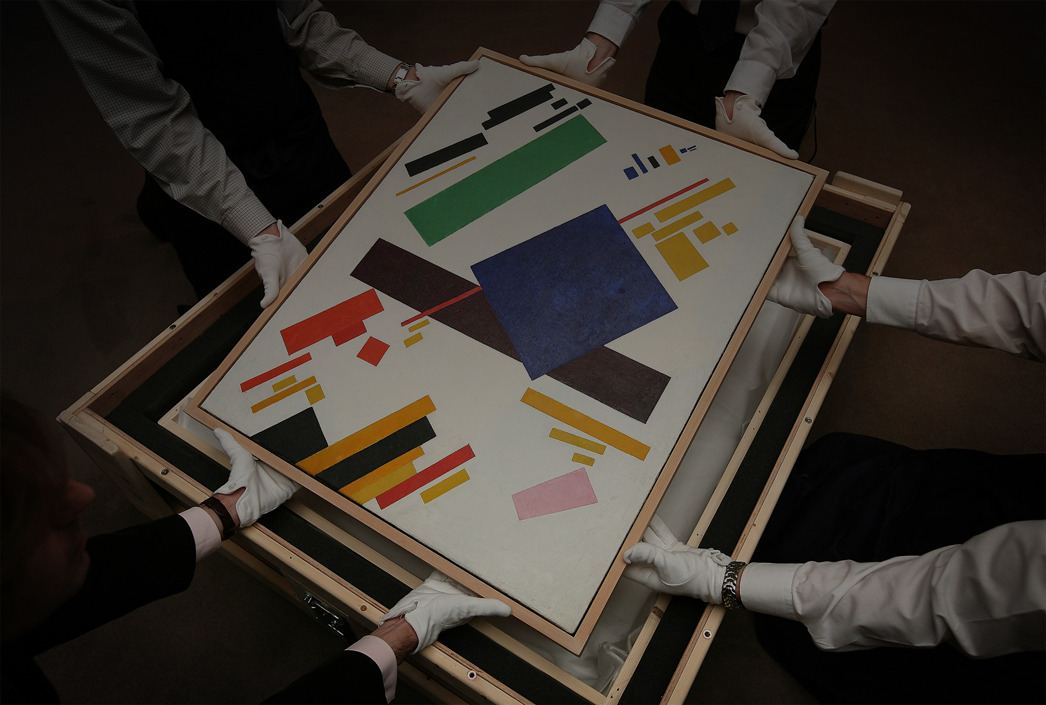

Moscow, 1988: Sothebys holds an auction of works of former underground artists. They drew huge sums for that time. The biggest hit is Grisha Bruskin’s “Fundamental Lexicon”, bought by a Munich collector for $461,000. Artists now realize their view of reality is completely out of sync with the global art market, and what kind of money people can make there.

The West had great interest in Russia then: festivals screened Russian films, theaters did tours, and many artists went West not for political reasons but from lack of money for their projects. That’s how Europe drew artist Ilya Kabakov, directors Pavel Lungin and Vitaly Kanevsky, and many more.

But it is soon clear that not all will be let in, and Russian art’s commercial potential in the West is not quite so grand. The “USSR fad” quickly fades away. Meanwhile, state funding dwindles with the USSR’s collapse. The state still must prop up the vast Soviet cultural infrastructure. Libraries in remote corners of Russia require support, as do regional theatres and museums. This was a huge state budget item, especially for the early ’90s when spending had to be slashed.

Many cultural institutions think about where to get money from, if not the state. In the early ’90s, this looks a bit naïve and idealistic. All await new Russian philantropists to magically appear – a new Shchukin, Morozov, Tretyakov – and fund theatres, galleries just for being there. This situation seemed better for art, as there would be no ideological dictates. One would get creative freedom. Now the state would yield to generous patrons granting total independence, not expecting anything in return.

Things are not so simple, it soon turned out. Patrons appear who are not so idealistic. There are few of them, and their motives are quite unlike Shchukin or Morozov. The word “philantropist” gives way to “sponsor”: someone you get to fund a one-time project in exchange for showing their logo or involving them in some theatre group. Sometime sponsorship was just envelopes with cash, which sponsors personally gave to their favorite artists. No one understood how it worked, no one had figured out any system for it.

One thing saved it: many Russian businessmen had come from the late USSR intellectual environment. They had inherent respect for culture. They knew their help might be unsystematic and odd, but they still had to help.

The first attempts are made to put private support on some solid ground. In 1992, for example, Boris Berezovsky launches the Triumph prize, a massive $50,000, for Russia’s leading and respected cultural figures. Critic Zoya Boguslavskaya heads a committee to decide winners.

There appear people for whom cultural funding is a real passion, it changes their lives significantly. Vladimir Ovcharenko was a successful financier, founder of the Europe Trading Bank. Perhaps for fun, he opens the Regina Gallery. It hosts among the most radical, provocative exhibitions of the era.

He gradually lost interest in banking. By the late ’90s the gallery’s his main job. Interestingly, in the long term this strategy proves the best. Few early ’90s institutions are still around now, but Regina’s doing fine. In 2010 it opened a London branch. Recently Ovcharenko launched the Cozmoscow art fair and the Vlady auction.

Western groups arrive in the mid ’90s. They work on totally different principles. They don’t just help their favorites or raise money for one-time projects. Theirs is strategy of advance planning for years, in all kinds of directions.

Soros’ Cultural Initiative and Open Society develop a new grant system for young scholars and students. 65,000 people receive these grants for 10 years. The foundations work with culture that generally cannot pay for itself. They open regional internet centers, support regional libraries, buy books for them, provide subscriptions to major literary journals. In 1997 Open Society, Ford and MacArthur fund the first year of Saint-Petersburg’s European University, one of post-Soviet Russia’s strongest institutions.

In 2004 Open Society ceases activity, but many projects it sparked continue today. In Saint-Petersburg the Pro Arte institute is still around. It undertakes many great projects for museums, architecture, music, and other arts.

Cultural institutions had to learn many new words. Thus, in the mid ’90s the word “fundraising” is first heard in Russia. This means activity to attract sponsorship and investment. Again, it is Western experts who coach Russians in this. Perhaps the first success was Mikhail Pletnev’s Russian National Orchestra, through the efforts of Amercan expert Patricia Ciraulo, then RNO deputy director.

The Golden Mask Festival, founded in the early ’90s by the Union of Theatre Workers, gradually expands. Through Edward Boyakov’s team it continually finds new sponsors.

Marc de Mauny arrives from the UK in the mid ’90s. With violinist Andrei Reshetin he founds the Saint-Petersburg festival Earlymusic. For some years, he successfully fundraises from many varied sources. Then he winds up on the other side, at Raiffeisenbank. He heads its PR department and decides what projects to sponsor. Then with Teodor Currentzis he goes to Perm and makes its opera Russia’s best, largely due to outside funds he manages to draw.

By the late ’90s most large companies were sponsoring culture. Fundraising went from guerilla tactics to systematic activity with well-known organizations that could provide these funds. The orgs themselves had to be wrecklessly bold as before, for this activity was hardly regulated by the state, and not supported by it at all.

The first attempt to legislate arts funding came in 1997 from then-Duma members Stanislav Govorukhin and Nikolai Gubenko, and Sovremennik Theatre director Galina Volchek. This project stalled for many years. The patronage law was adopted only in 2014.

This law at least defines patronage, notes its slight difference from charity, yet rewards to patrons it sets out are commemorative signs, diplomas, awards, memorial plaques on buildings they sponsored. Nothing about tax breaks or other economic incentives.

For someone to support and fund culture in Russia, some powerful incentives are required. Just like before, everyone finds their own. For some, it is about realizing their own ambitions. Vladimir Kekhman, one of the largest fruit importers, becomes director of Saint-Petersburg’s Mikhailovsky Theatre in the mid 2000s and provides funding for it, clearly driven by his own unrealized artistic dreams, the chance to take photos with Elena Obraztsovaya, or even go on stage during a ballet.

For some, this is a big boost to their reputation. Roman Abramovich founds the Iris non-profit, which funds the Garage center, film and educational projects, and also rebuilding New Holland.

For some, it is what Putin’s Russia calls “business’s social responsibility”: when the state asks business to fund a project of national scale and importance. Alisher Usmanov buys from American actor Oleg Vidov the Soyuzmultfilm library. He later wins Mstislav Rostropovich’s and Galina Vishnevskaya's collection at Sothebys and returns it to Russia.

The foremost strategy may still be an inner passion, even collector mania. Many Russian collectors found institutions greatly expanding the cultural space. These are museums and organizations that would never get state aid. For example, businessman Boris Mints opens a Russian Impressionism museum based on his own collection.

Many businesspeople fund large cultural projects they feel reflect the zeitgeist. Alexander Mamut opens the Strelka Institute for media, architecture, design. Yota founder Sergey Adonev funds the Stanislavsky Theatre renovation. He opens there the Electrotheatre led by Boris Yukhananov.

Whatever motives guide modern patrons, the state can sometimes get in the way. The Dynasty Foundation was started by Dmitri Zimin, founder of Beeline. In the 2000s it supported Russian science, awarded research grants, organized science festivals, and published pop sci books that created a new niche in the book market. Ultimately in 2015 Dynasty was named a foreign agent on a technicality: Zimin’s money for project funding came from his foreign accounts.

But what is absolutely certain is that this conflict, the relationship between the artist, the cultural institution and the person with money, hasn’t been reflected in the culture. Thus, society is still unaware culture’s a responsibility of business, that the two should have a natural partnership, not a haphazard symbiosis.

Clearly, nowadays patronage is not a game with a guaranteed result. It can all end for any reason, economic or political, at any time. Probably the strongest driver is not cold calculation but plain strength, faith, passion. Not expecting tax breaks, public applause, but the mere desire to do something great. Something that remains after you are gone. Something that your descendents will use and enjoy. Just like in the days of Shchukin, Morozov, Tretyakov.