Between “Segodnya” (today) and “Zavtra” (tomorrow)

Short history of media

Experts: Yuri Saprykin

Short history of media

Experts: Yuri Saprykin

Short history of media

February 23, 1993 saw the first issue of a new daily newspaper, “Segodnya” (today). If you don’t remember 1993, it’s probably hard to understand what the launch of a new daily meant back then. First of all, a newspaper was a huge event, something precious.

A good paper was worth lining up for from 7 a.m., as happened in the late ’80s with Moskovskie Novosti.

Likewise, a good TV show was worth waiting until 2 a.m. for, waiting until Vzglyad revealed something new about Stalin’s crimes.

A good lit mag was worth using almost all the country’s paper on and letting millions wait six months for the next issue, but in it “The Gulag Archipelago” would be published.

Sometimes a good journalist can change the fate of the nation. Like August 19, 1991 at a press conference by SCSE members. The young reporter Tatyana Malkina for Nezavisimaya Gazeta asked, “Do you understand that you’ve led a coup?”. After that, things did not go well for these men.

A good new newspaper is always a new good language. Through the late ’80s, USSR media sought to escape the staid Soviet style and think up a new lingo.

Kommersant, which arose in 1989, had a dry style, where articles consisted only of facts, emotion-free, and at most were supported by references to anonymous Kommersant experts. However, it ran funny headlines and Andrei Bilzho’s Petrovich cartoons.

At Nezavisimaya Gazeta from a year later, the editors studied Financial Times and Reuters style guides, and thought up a new headline format. They did everything to write for their new readers in a truly new language.

The Segodnya style had artistic flair under literary critic Boris Kuzminsky. It printed film reviews in chess study form, and after “Twin Peaks” came out, it studied the series culturally, analyzing its most suitable quotations and sources.

But an artistic element wasn’t the only important side to them. The paper gathered all-star journalists: from Sergei Parkhomenko to Mikhail Leontyev. This was clearly a major endeavor with serious aims. These aims had a name and surname: Vladimir Gusinsky, one of the major Russian bankers, who personally founded and owned the newspaper.

This was something new for Russian media: the newspaper wasn’t just a way for journalists to pontificate, but a business that should generate returns.

This was the approach of Kommersant, Nezavisimaya Gazeta and Segodnya, soon joined by Gusinsky’s new assets: the NTV channel, the weekly Itogi, the NTV+ satellite channels, and finally radio station Ekho Moskvy. These were all incredibly professional, home to the era’s best journalists. It all looked like Gusinsky sought to build a huge media empire. One that was successful, profitable, and might become the foundation of his business.

Not all 1990s mass media, it must said, shared the optimism. An opposing view of the nature of this profession existed. For example, Den’, launched in 1991, positioned itself as an opposition paper, and it didn’t conceal that its aim was to fight Yeltsin’s criminal regime, which was leading Russia to capitalism at the West’s behest.

After the 1993 White House events Den’ folded, but it was immediately resurrected under the name Zavtra and started to attack the criminal Yeltsin regime with renewed force.

One of Zavtra’s regular contributors, writer Eduard Limonov, then launched his own Limonka, the official newspaper of a new National Bolshevik Party: a paper with a more radical, youthful aesthetic, but the same promise. The publication did not hide its being propaganda, a tool to fight the new bourgeois values and the world of the adults sunken into evil.

In the mid ’90s, these publications all seemed relics, remnants of the Soviet empire, attempts to return history to a place it couldn’t go back. But the future was in the hands of others entirely: the young and energetic media entrepreneurs who spoke the new language.

As befits any business, a media business seeks and sometimes creates new, unfilled niches. In the process, they discovered incredible new formats. It turns out that TV can show debate programs, opposing different points of view. This becomes known as the “talk show” and appears in prime time.

Radio stations discover they can banter between songs, and you can call in live, and the presenter will let you say happy birthday to your relatives, and almost the whole country will hear it. Many new possibilities are discovered by the glossies: dozens are launched over just a few months. In Playboy under Artemy Troitsky, half is half-naked beauties, the other half serious prose from authors like Viktor Yerofeyev.

Domovoy was the first to introduce the concept of the “New Russians”. This was a magazine meant specifically for this new class. It described their mores and tastes, although it presented them in a slightly idealized form.

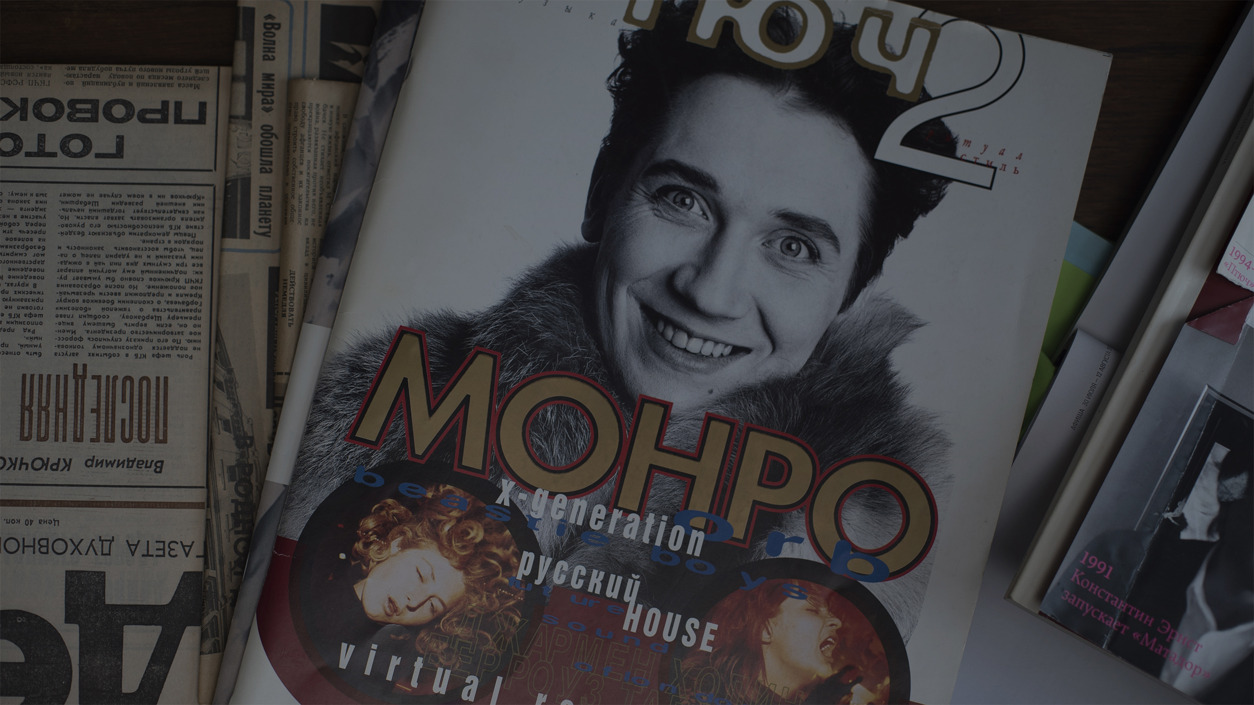

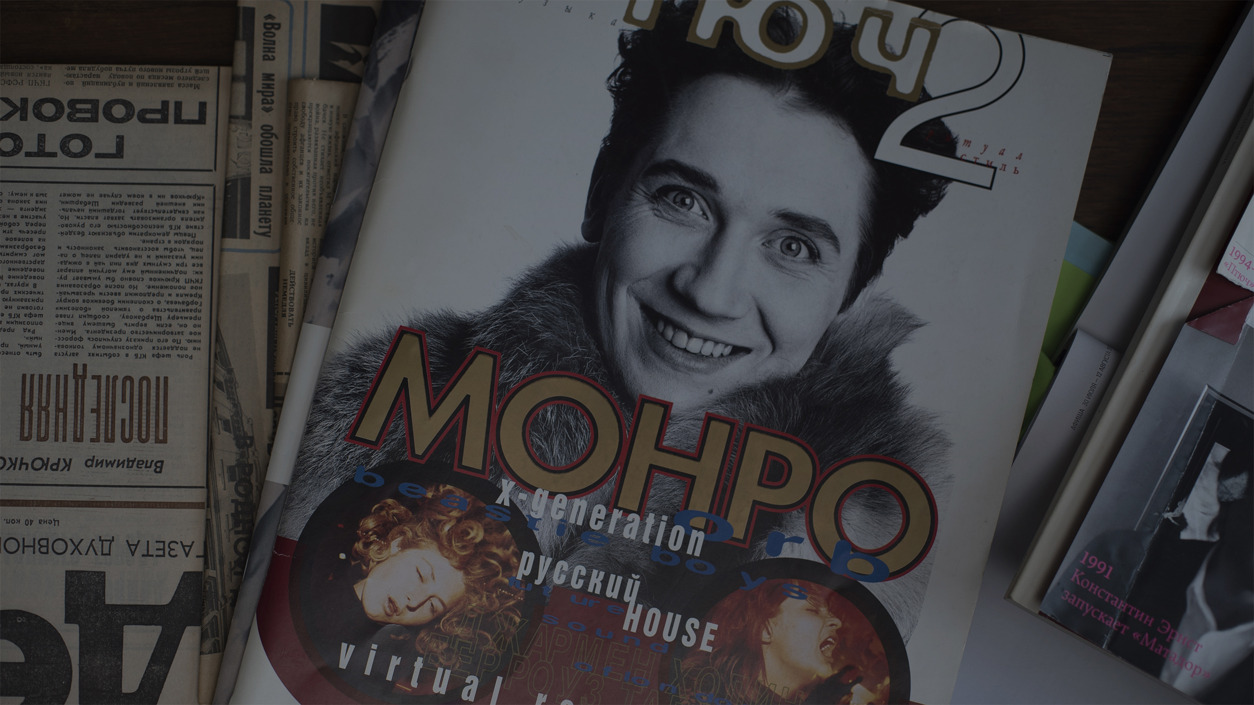

OM was a magazine for those soon to be dubbed metrosexuals. For those who wanted to know more and live better. Ptyuch was something completely wild: a psychedelic publication of the new culture of parties, “raves”. This was reflected in its wacky layout, that was part of the game.

Perhaps never before in the 20th century had Russian media enjoyed such freedom.

In the new Russia it must be said the journalists of these free media were the main beneficiaries. They had an interesting job, good pay, a huge sense of demand and incredible freedom. Thus, as soon as a threat to this new reality arose, they sacrificed their own freedom to defend it.

This happened in the time of the 1996 presidential campaign, when a group of Russian oligarchs took Boris Yeltsin from 3% approval on January to election victory. Now some of the new progressive, independent media suddenly began to speak a completely Soviet propaganda.

From Kommersant arises the newspaper Ne Day Bog! This is open agitprop that exposed the Communists, caricatured Zyuganov, and wrote about how bad life was in the USSR. It is dropped through mail slots for free, printed in runs of 10 million copies.

The nation’s main TV channels laud Yeltsin nightly, and note how bad his opponent seems in comparison. Igor Malashenko of NTV management even goes to work for Yeltsin’s campaign, without ending ties with the channel.

Days before the election, ORT airs the most popular broadcast of the era, Polye Chudes, featuring figures from the competing NTV channel. These were puppets of leading Russian politicians. They spun the wheel and the winner was naturally Yeltsin.

At that moment, perhaps, media magnates felt not only an opportunity to pitch new bourgeois values, not only a potential profit, but also a huge tool of influence that could be used for their tactical goals. Once one starts doing that it is very difficult to stop.

After elections, Gusinsky and Berezovsky used ORT and NTV to publicize the Svyazinvest case. They weren’t happy with the company’s loans for shares results. They took revenge on Anatoly Chubais et al., accusing them of taking bribes.

In the next presidential elections, propaganda was again turned to max. Now however the former partners were on different sides. Gusinsky’s NTV moderately supports Luzhkov and Primakov. Berezovsky’s ORT charges at them with the same fury that it had lambasted the Communists before. The main hero is Sergei Dorenko. In his evening show in its information program he reports of Primakov’s operation abroad and how bad he felt, and about how Luzhkov was involved in all sorts of crimes.

A key trick was to discuss some irrelevant story, and then rhetorically ask: might Luzhkov be involved?

As a result of the program, Dorenko achieved his aims. The Luzhkov-Primakov bloc was defeated in parliamentary elections. But several months later, defeat came to Dorenko himself, the owners of his channel, and the competing channel’s owners.

When Vladimir Putin came to power, he realized the power of the oligarchs’ media. Among his first acts was to oust them from control of central TV.

Gusinsky even found himself under interrogation and signing over his shares in his media business. Berezovsky was forced to leave the country. Dorenko was forced off air after reporting on the Kursk submarine tragedy. Putin was convinced that the “sailors’ widows” were hired actresses and it was all a provocation against Putin personally. In April 2001, masked men raid NTV and new management comes in.

Then, most employees of this unique team left the station. When Putin was asked to save the channel, he said he couldn't interfere in an ownership dispute.

In later years, any big TV channel, newspaper experienced the same scenario. Any political crisis – Nord-Ost, Beslan, Chechnya – the state uses to accuse the media of subversion, undermining national security. This forms grounds to change management, or make ownership pass to state-friendly figures. Yet the highest authorities claim they have nothing to do with it, and they won’t get involved in “ownership disputes”.

By the mid 2000s, all major TV was controlled by companies close to the state. Politics gradually disappeared from them.

Their audiences, it must be said, made no complaint. People were clearly weary of the information war. When Dorenko and Kiselev gave way to police procedurals, or Andrei Malakhov’s talk show, people were glad.

By the mid 2000s it seemed that large federal media were state-controlled, and large holdings like Gusinsky’s Media-Most were no longer possible. But there remained many specialized, niche publications, where honest, independent journalism was quite possible.

There are publishers with foreign investment, who publish Vedomosti and Forbes, Russia’s best business newspaper and magazine. There are honest and high-quality glossies: GQ, Esquire and Snob magazines, where ever more unbiased sociopolitical journalism appears.

Ultimately, there is the internet. In the mid 2000s the state did not know what to do with this media, or whether they had a significant public. Thus, even large internet media companies, even the news websites Lenta.ru and Gazeta.ru, enjoyed relative freedom.

Moreover, all realize that the internet is the future, so it, gradually attracts big money. Ever more new ventures, independent resources arise. It seems that this configuration might go on forever. But after Bolotnaya Square and Putin’s third term, things changed sharply.

Obviously several factors came together: from the media's economic crisis (not only in Russia) to the new and restrictive legislation quickly adopted. The result of all this was the same: what the journalism world calls the “damned links in the chain”: endless resignations, closures, layoffs, and a shrinking space for independent journalism. There is still no end in sight.

Investors in that media feel much less at ease, for print runs drop, the internet takes over where it isn’t clear how to monetize, and media goes from potential profit to potential problems with authorities. Mid-2010s people tend to invest in e.g. Spas TV or Tsarigrad TV, so patriotic, Orthodox TV. There’s not much money in it, but you can position yourself as a responsible, patriotic businessman.

The internet also attracts especial attention and control from the state. Roskomnazdor introduces ever more restrictive measures on not only journalism but social networks. Large media companies attract action by the authorities.

In a single spring 2014 day, after a warning from Roskomnadzor, Galina Timchenko is removed as Lenta.ru editor-in-chief. After it, the entire editorial staff leave, and the headlines of this chief internet news source change drastically.

Of course, there remain spaces where independent reporting is possible, but each space must seek its own way to survive. Slon.ru, Colta.ru, Novaya Gazeta, New Times, Dozhd TV – are practically all funded with no expectation of return or experiment with paid subscription or crowdfunding. At any time, they may be targeted by the state for offending someone’s feelings.

As for big, federal media, the state clearly does not want to entertain a public. It seeks to control minds. Ukraine’s crisis sparks a need for a new mobilizing ideology, but one is already at hand, long prepared by Zavtra and Limonka, which 20 years ago had seemed old Soviet relics. Aggressive nationalism, opposition against the West, a strongman cult, a strong state – this proves to be in great demand and moves from marginal newspapers to TV prime time. The main news and talk-show hosts now speak like Limonov, Prokhanov. They present their image of the future to audiences.

Strangely, in 2010 we’re back in the yesteryear that Zavtra envisioned and which Segodnya sought to escape.