Opening of the Olympics

Russia that we didn't gain

Experts: Yuri Saprykin

Russia that we didn't gain

Experts: Yuri Saprykin

Russia that we didn't gain

Yuri Saprykin: On July 5, 2017 at 3:18 a.m. Moscow time, Guatemala gymnast Anna-Sofia Gomez hands an envelope to International Olympic Committee chairman Jacques Rogge. Rogge opens it, takes out a card and turns it to the cameras. Competing to host the 2014 Winter Olympics, Sochi vies with Austria’s Salzburg and South Korea’s Pyeongchang. At the IOC’s 119th session to choose the hosting city, an impressive delegation represents Russia. It is headed by Vladimir Putin. Russia’s president speaks in English and ends with a French greeting. Putin promises that Sochi will be a new world-class resort for a new Russia and the whole world. In the second round, Sochi gets 4 votes more than competitor South Korea. Sochi residents, gathered before the city’s Winter Theatre, react with jubilation.

Alexei Levinson, sociologist: It was hugely important for following events, the fact at the IOC a battle was won, our side won. The public saw this as a victory for Putin.

Saprykin: By the next morning it’s clear that not all are overjoyed. Callers on morning radio, LiveJournal users say the money spent will inevitably be stolen, and better it were spent on something more useful to society. For example, higher pensions for the elderly.

Levinson: As people were saying then, and polls showed, did Russia have nothing better to spend money on than the Olympics? This view was upheld by some Russians, rejected by others. This in fact reflects the two positions common to Russians’ thinking. One side is the intelligentsia, the so-called educated class. The other side was the part of society in disagreement with them. The public opinion leaned to one side or the other. So, the public either support spending the money elsewhere, on healthcare or schools, or they say this is something necessary to make Russia strong.

Saprykin: Corruption, utter theft during Olympics construction, was a subject of wide discussion even before the Olympics. Boris Nemtsov gave a speech in May 2013, “A Winter Olympics in the Subtropics”. The politician estimated that 50 billion dollars had gone to the games, over half of which was stolen. Shortly before the games, Alexei Navalny’s foundation launched a site dedicated to the Olympics. The games’ costs were estimated at 1.5 trillion rubles, five times more than the Vancouver Olympics, ten times more than the Torino Olympics. The Ministry of Finance says the sum was much less, about 214 billion rubles. Of that, 114 billion came from private companies. However, the 1.5 trillion ruble amount was confirmed by prime-minster Dmitry Medvedev, though he said that was for the development of the whole region.

Kirill Rogov, political scientist: A collision with the Olympics began 1–1.5 years before the games themselves. It was so fateful in a political sense. The issue was stated as follows: either the opposition or the West will prove that the Olympics were mainly for corruption, or Putin will convince the nation that corruption’s no matter if such a fine event is held. Those were the two likely outcomes. Both sides were prepared for that. The opposition came out strongly, e.g. “Two toilets in one stall!”. Such an image of corruption unfolded. Corruption stood at the center of it all. On the other hand, huge efforts were made to downplay corruption. It was a big political battle.

Saprykin: No one hid that Olympic construction was wasteful, though. Everything had to be prepared in a very short time, in an unideal climate for winter sports. To hold the games, Sochi’s entire infrastructure had to be rebuilt, and several miniature towns too. The Olympics was partly meant to show Russia could handle big projects, no worse than other highly developed states.

Alexander Baunov, political scientist: Of course, the Olympics were meant to be Russia’s big ticket, its growing up. Because, what is this? In a normal country, we’d be approaching the end of the Putin era. He came to a Third World country, and now he can present to the world a proud developed nation with skyscrapers, high-speed trains, well-dressed citizens doused with fine perfume.

Maria Lipman, political scientist: In the run-up to the Olympics, when the Western media covered Russia’s preparations, one sensed a strong prejudice, a desire to see only negative things. Of course, human rights issues were put in the spotlight. One key thing was that when preparations were in the final stage, the anti-gay law was adopted. There was even an attempt to boycott the games, or at least organize some effort to protect the gay people there. This wasn't done, partly because the Olympic Charters forbids politicizing the games.

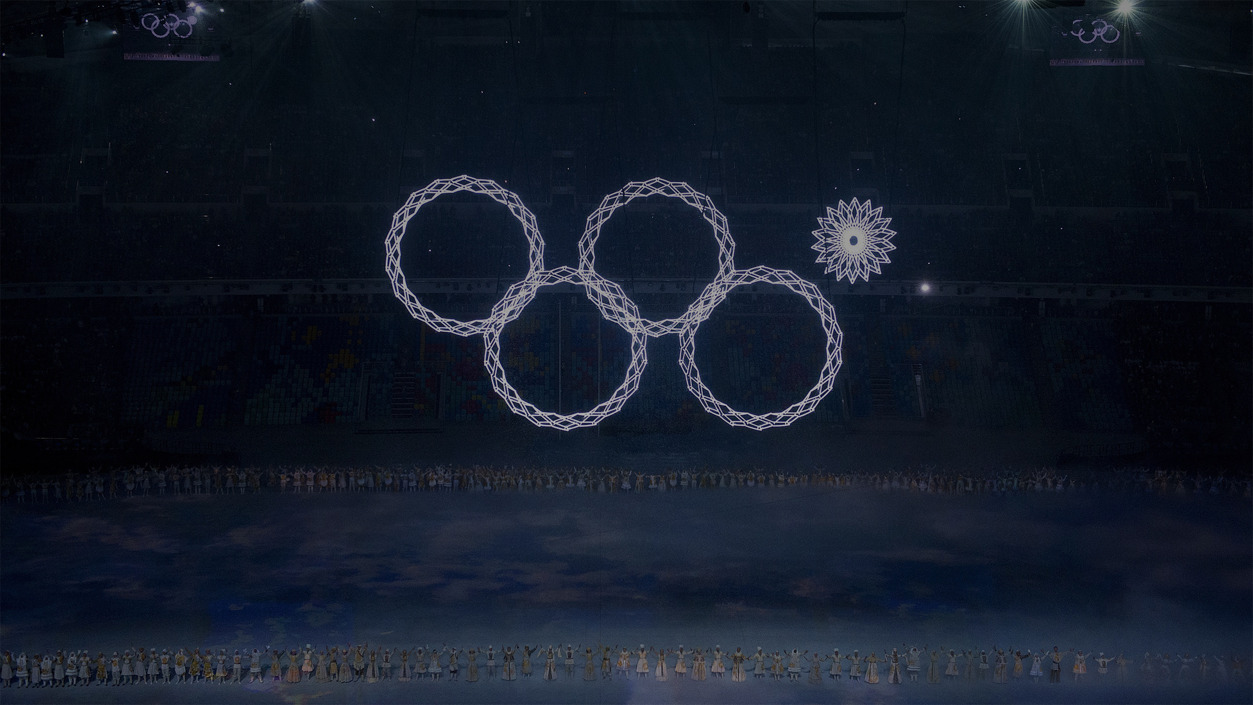

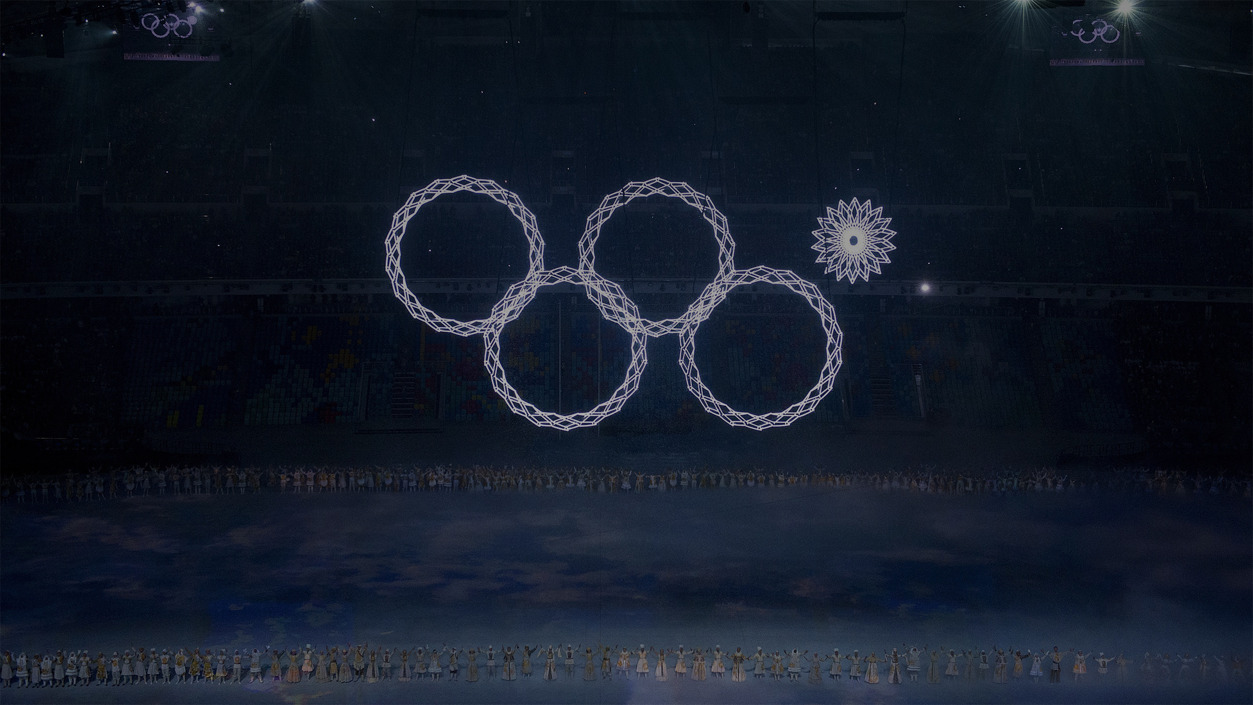

Saprykin: On the evening of February 7, 2014, all Russian channels broadcast “The Russian ABC”. The 11-year-old gymnast Liza Temnikova from Krasnodar recites the alphabet. Each letter was related to something Russian: S for Sikorsky’s helicopter, Y for Norstei’s cartoon “Yozhik v tumane”. M for Malevich, N for Nabokov, and E for Eisenstein. This was the start of the grand opening of the games. It presented a side of Russia unexpected today: a country where it’s not power and religion that matter, but great literature, ballet, Futurism, little Lyuba’s enchanted dreams of Russia. It was all so high-tech, impeccably organized. Well, except for one of the Olympic rings not opening.

Baunov: During the games I remember two kinds of joy. One was the common societal joy at winning medals. The other was specifically of the intelligentsia, of those who weren’t sports fans, who don’t care about goals, points, medals. I’m talking about the ceremony, which was a separate event.

Lipman: The 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics were a sort of anachronism. It was initially conceived as a way to impress: Russia would show itself as attractive, modernizing. In terms of the opening, it was a Russia with cutting-edge tech, big spectacles. It showed itself as a country of culture. Note how they chose Russian culture familiar to Western viewers: Tolstoy, Stravinsky, a Russian avant-garde painter, Bulgakov. These are readily recognized in the West, and represent something good about Russia. They invited George Tsypin to design the staging. He’s an emigre, from Russia but long resident in the USA. He’s a renowned designer with a great track record. But inviting him was an anachronism, too. If Sochi Olympics planning started in 2011–2012, I think it would have looked different. Other people would have been hired, other symbols used. Quite likely other episodes of Russian history would have been used. It would have been more militant.

Saprykin: The game drew huge interest from TV viewers. The Sochi games made up a third of nationwide broadcasting. During breaks, viewers watched news reports, where Olympic victories alternated with Kyiv Maidan scenes. In the games’ last days, Russia was #1 in medals won, which sparked huge patriotism and record ratings for Putin.

Rogov: We didn’t know something then: the Olympics would play a key role in Russia’s political future. The population’s loyalty to some regimes directly correlates to those regimes’ TV audience numbers. They don’t allow other points of view on TV. Normally, democratic people would watch TV and think, “Hmm, am I for this or for that?” Here there is only one perspective. In that situation the average man can choose: he either sits at the TV, or he walks away.

When he walks away, doesn’t care about the news etc., the authorities’ ratings start to fall. They are less able to indoctrinate viewers, so loyalty falls.

If we look at February-March 2014, from the dawn of the Maidan, Crimea, etc., we see people gradually sucked into the political agenda through TV. It started with the Olympics. TV won people over at the Olympics, and then it set them up for the Ukraine conflict.

Saprykin: The games’ closing was held on February 23, the day after Ukraine’s president Viktor Yanukovich fled, and Maidan activists took control of the state. In the evening, Kyiv crowds met at the Maidan to say farewell to the slain Heavenly Hundred. These days saw Russia’s special operation to annex Crimea. Russian TV viewers had just been thrilled at sports victories, and now a new grandiose spur for national pride began.

Levinson: These victories had a peculiar aspect to them: we won in something we weren’t overtly playing for. That’s important for the new concept that has formed of the Russian state, Russian power.

The events after the Olympics rhyme with those after Eurovision. The first thing that rhymes, is that Putin’s rating then rose to 88%, and now it rose to 88%, and then even higher, but to 88%. Then, the reason was a military victory. I hope viewers remember which one. Now the reason was a quasi-military victory: one won by people in uniform. They tried not to call them soldiers, they used various euphemisms: “little men”, “polite people”, but everyone realized they were military. Again, it wasn’t what we were expecting.

Baunov: It turned out like this: people high on sports victories were willing to accept the military victories. Yes, willing. I think that even if Russia was defeated in the games, they’d still be willing. Clearly these people were basically ready. They’d say judges were wrong. They’d say it’s all because the great Soviet sport collapsed. But what is annexing Crimea compared to sporting defeats? It’s a compensation. Yes, we made a mistake, Soviet sport fell apart, but now we’re back. It’s like the graffiti about Gagarin: “Yuri, we pissed it all away” and “Yuri, we’ll get it all back”. Yes, we’ll get it all back.

Saprykin: The Sochi Olympics should have been the political and cultural smash of the 2010s. Just months later, it is overshadowed by tragic events. Today few remember the grandiose opening. The one evoking the glorious Russia of Malevich and Nabokov. It was overshadowed by the “Russian world” of Strelkov and Motorola. We lost any ticket to developed country status, instead we’re under sanctions, isolated internationally.

Lipman: Well, thank God the dour predictions didn’t come true: no terrorist attacks, the roads did not collapse. As the preparations showed, Russia knows how to burn the midnight oil, in a situation with tough deadlines, but they must be met. They managed to do it. Plus, Russian athletes did well. As the games ended, I’d say they looked better. You had to admit they were put on well: the ceremonies, the Russian athletes, the Olympic Village, at the venues. But it was too late, because the impression of the games changed, but not that of Russia.

Baunov: Alas, the Olympics proved no big ticket for Russia, no growing up, no showcase of an open and civilized country. Because it coincided with the Maidan, it proved this: no matter how the Russians dress up, no matter what image they broadcast, what fireworks they launch, what pianists they show off to the rest of the world, and regardless of the high culture they point to this is what they really are.

Levinson: In popular consciousness there are two types of appraising things. They can be associated with appraising one’s work and one’s great deeds. Inasmuch the Olympics were an economic thing, you can ask: How much did you spend on them? Or how much should you have spent, and how much did you steal? Does anyone ask about a war: How much does the war cost? Or at least how much our help over there costs. It’s obviously a lot, but real help ought to cost a lot. You need to have a cool head, stand apart from the crowd, to ask questions like: How much will helping the Donbass cost us? How much will the Olympics cost us? Well, we can afford it. It means we’re not going to count. We can afford it. We have afforded it.